Running 101 – Basic Running Types Part 3: Recovery Runs

Base training is a tricky business. A lot of it is about loading up on mileage and some runners like to sneak in the extra miles by turning their recovery days into “recovery runs,” even though it doesn’t do you any good at such an early stage of your training. Proper recovery runs are the ones that follow high-intensity workouts and long distance runs – basically, just remember to balance hard runs with recovery.

In the past, there’s been a lot of confusion about why runners should be doing recovery runs. Coaches, personal trainers, and both casual and serious athletes alike have come across the same misconceptions: recovery runs flush out lactic acid build up, it can help prevent delayed onset of muscle soreness (DOMS) – purportedly also caused by lactic acid, and it promotes recovery… but there’s actually very little evidence supporting any of these. Not to mention, lactic acid is actually a secondary source of energy in the absence of oxygen. So what’s the point of doing these recovery runs?

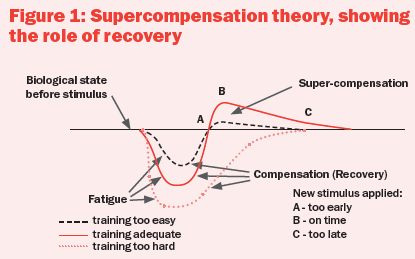

The above chart shows the “supercompensation” theory, which suggests that our bodies are able to adapt and become stronger following hard runs with adequate recovery. Much like heat-training, the role of recovery runs is to teach your body to adapt to certain physiological stresses so that you can perform better in subsequent runs. Or, to put it differently, you’re essentially learning to run more efficiently at a pre-fatigued state. Check out this “fresh perspective on recovery runs” by Matt Fitzgerald – it’s got a wealth of information on why and how runners can benefit from these types of runs. To summarize some of his best practices:

- key workouts (high-intensity training and long runs) should be followed by a recovery run

- recovery runs only make sense when you run 4x/week or more

- when you regularly do high-intensity training, your hard run to recovery run ratio should be 1:1

- the length and pace of a recovery run depends on the runner (“there are no absolute rules”)

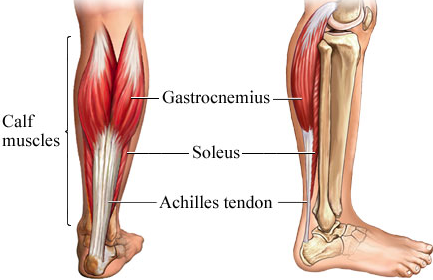

It’s also important to keep in mind the nature of specificity: our muscles, with enough repetition, adapt specifically to the type of stress we subject it to. Think of recovery runs as a way of acknowledging fatigue and finding ways to break through it. Think of the runner that trains for a marathon by running 27-miles before the race. These runs are supposed to be pretty easy. Don’t sweat it. Literally. And remember that adaptation takes time. Respect your limits and know when to cut back. Remember, you’re supposed to be recovering 😉

More background on exercise adaptation from Thomas Fahey’s, “Progressive Resistance Exercise.”